Surf and the Art of Career Navigation

Disclaimer: I am as good as a surfer as I am experienced a professional. I like to think I’m intermediate at both, but realistically speaking I’m probably a novice… This post started out as some therapeutic musings, but then I put more time and energy than expected, so I decided to polish and share it. Either way I hope reading it provides a bit of an idea on what surfing is, or maybe you get a fresh perspective on your career path. Or maybe neither… Or both. Just read it!

As background to this post: I have been surfing for about 5 years and I’ve been working for about 10 years. Maybe it was the COVID-induced confinement to my home in the Netherlands evoking some feelings of withdrawal and longing for surfing, maybe it was the slight burnout that forced me to take some distance from my job, and it’s definitely some coping mechanism, but I recently started seeing a lot of similarities between surfing and careers… Both in surfing and in our professional careers success is the result of putting in work, making the right decisions and having a bit of luck. I’ve written down these thoughts when it became clear to me that just like in surfing, in our jobs we sometimes put energy in something where your energy is not spent optimally and just taking it easy and taking a step back might actually end up working in your favor.

I’ll write down my observations following the three main activities a surfer engages in when they surf, which are: 1) paddling: for getting to the break, positioning in the break and actually catching waves. 2) riding waves: because that’s like the ultimate goal isn’t it? And 3) exiting waves, because all good things come to an end.

Looking at my career so far in this way, I can clearly see that I’ve paddled (at times not hard enough, at times way harder than necessary or even helpful), I’ve ridden (sections of) waves and exited a couple of waves (some of them more elegantly than others).

On with the musings…Because before you can ride, you have to paddle.

Paddling to Catch the Wave

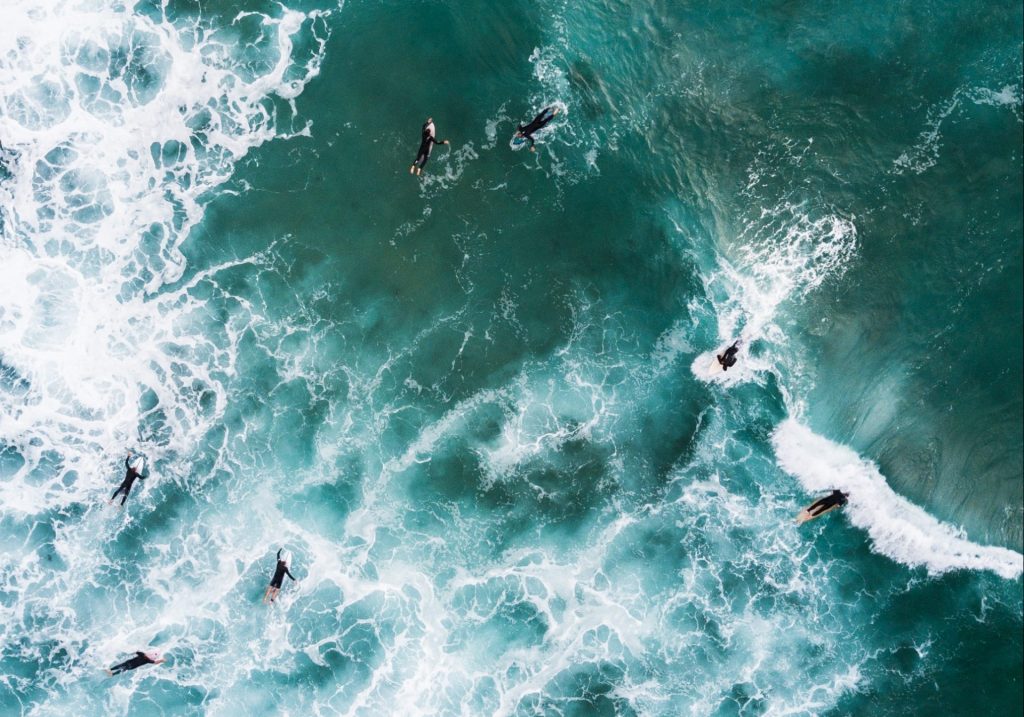

The image people normally have of surfing is that of someone standing on top of a surfboard, shooting across the face of a wave and doing sick manoeuvers. The thing I quickly learned from surfing is that actually standing on your board makes up actually only 5-10% of surfing (and in full honesty, you only get to those numbers after a couple of years of 0%). The rest of the time surfers paddle, for one of three reasons: getting out the back, positioning and catching waves.

First of all, surfers have to paddle to make it ‘out the back’, or to reach the point beyond where the waves break and turn into white water. This is where you can find these clean faces of the wave to ride. It’s hard work to get out the back. Depending on the size and power of the waves this can take an enormously long time and depending on how well a surfer can read the ocean, they might actually take infinitely long. In some cases people start paddling into a current going towards the beach, making it next to impossible to get out. More experienced surfers will look for rips, where underground channels provide a way for water to go back into sea, resulting in a current that actually takes us out the back almost automatically. If they spend some time looking at the waves from the beach they can identify where the rips are and make their lives easier. If they don’t look it’s kind of a matter of luck or unnecessarily hard work.

Secondly, surfers paddle do it once we’re out the back to position for the right waves. Waves break in different places and on beach breaks especially, the contours of the bottom are changing all the time, which results in continuous changes in the place where waves break. Similarly, as the wind or swell direction changes, or as the tide goes in or out, the waves will start breaking further out, further in or in different places. To account for these continuous changes, while waiting for waves surfers almost continuously paddle to reposition themselves to be in that one right spot where a wave can be caught.

Finally surfers paddle to catch the wave. But in all honesty, paddling for catching a wave is as much part of riding as it is of positioning. Once a surfer’s in the right spot, and sees a wave forming behind them, they start paddling to catch it. They have to commit to the wave, dig deep and get ready to ride it. They first start out with normal paddling to match the speed of the wave and then they finish with a couple of hard, strong power strokes once the wave catches up with them to get that extra little push right before they pop up to their feet and ride the wave.

When looking at our careers, we spend a lot of time and energy in obtaining education. This is quite similar to paddling to get out the back, we’re not riding a wave yet, but we’re getting to a place where we can start catching waves. And just like a surfer can choose when and where to paddle out, we can decide what program we follow. We can decide how hard we work during our program and where we hope to end up.

But either way, studying is hard work that takes a long time. And much like surfers, some of us realize that sometimes it’s better to stop trying to get out in one place and head back to the beach and try from another place. No need in staying in a program where you will probably graduate, but it will take more of a toll than strictly necessary. On the other hand once we have finished our education and are out the back, it’s not like we sit completely still… We can keep on adjusting our position with non-educational professional activities, like networking, building a portfolio, getting your name out there through blogging/vlogging, basically anything that helps us catch that wave or land that job we want.

And once we’ve built all the credentials to land a nice job, we need to paddle to catch that wave. This final push of paddling, with the power strokes, right before popping up is the whole job application process. When applying to a job we always do some paddling: at the least by spending some time reading up on the organization we are applying to so that we know what to emphasize during our interviews and what questions to anticipate. And the power strokes even allow us to make some slight corrections as there is still some time and energy we can invest to correct for suboptimal positioning: we can use this moment to educate ourselves on the domain of our future employer or take a quick online course or training. Regardless of how we pop up, it is crucial to commit to a wave. In order to catch the wave you have to give it your all, it should be a conscious decision and you put your head down, dig in and you hopefully end up somewhere where you can reap the benefits of your work: you’re on top of a surfboard riding your wave.But then after that bit of paddling it’s hit or miss. Either we pop up and we’re hired, or we pull out and keep on looking. If we’re hired, we get on our feet and the fun part comes: riding the wave.

Riding the Wave

Now the fun starts! You are on top of the wave. You can shift your weight to your toes or your heels and slowly your surfboard turns and moves in the corresponding direction. You can shift your weight to your front leg or your rear leg and your board either catches more speed or slows down ever so slightly. All of these minor shifts allow you to control your place on the wave, speed and direction and in doing so you can go up the face of the wave, you can go down the face of the wave, you can move yourself into the pocket of the wave, where you can generate even more speed, or you can slow down. If everything works well you can do cool maneuvers and life is good. This is where things are fun! You have the thrill of riding, freedom to decide what kind of lines you draw on the wave and you get some attention, people looking at you, occassional nods of approval or shouts of support. But it’s not just balancing and riding, you have to keep an eye on the wave ahead and behind you.

Just like on waves you can control your speed and direction in your career. Aiming to make a promotion? Work hard, invest some time and energy and basically move towards the pocket of the wave where you can pick up speed and wind up for a sick move or hit a sweet barrel when the opportunity presents itself. Want to chill a bit more because you turned mom or dad or someone in your family needs care? Just go down the face of the wave where things are a bit calmer, pressure is a bit less, but where you can easily get back up into the pocket if you want to.

Now one limitation to riding is that despite all control a surfer has of his speed and direction, it is limited by the fact that waves are not consistent, monolithic things… Instead they are made up of sections. A wave collapses onto itself in different places along itself, so sometimes when a sufer is comfortably cruising along they see the wave ahead of themselves starting to break and they might actually not make it across to the next smooth section of the wave. So they keep some situational awareness to anticipate their next move: speed up, slow down, do a sick turn…

And similar to waves in our jobs we should be keeping an eye out for signals about how you and the job are developing and if there are moves to be made. Maybe everything is going along nicely and you can just sit back and ride straight and smooth for a while. Or maybe you want to do a sick move on the wave and have people notice what you do. Or maybe you notice the wave ahead of you starting to collapse, but there’s a nice smooth, glassy section further down the wave, so you readjust, speed up, give it an extra push and make it to the next section to continue on riding. We can do the same thing, work a bit harder on that report or that paper or bring one of your projects to an absolute brilliant end and end up in a next period of calm where you can relax and check out the wave a little bit again. Or maybe you realize that this wave is not even that good, maybe it’s not big enough or too big, maybe it’s not smooth enough or maybe it’s too smooth… Maybe the wave dies out or it knocks you off your board. Whatever happens, a wave might have nothing left to offer you anymore and you should exit the wave. And that brings us to the final part of surfing: exiting waves.

Exiting the Wave: Wiping out, Kicking out or Riding it Out

Now there are only three ways to exit a wave, which are, in order of most desirable to least desirable:

- Riding it out, or staying on the wave until it dies out close to the beach;

- Kicking out, or getting off of a wave before it dies out;

- Wiping out, or involuntarily getting off of a wave before it dies out.

So riding out a wave is quite straightforward. You’re on top of your board, going along a wave and enjoying life. And at some point the wave just dies out; It loses its momentum, there’s no power, there’s no height and you’re back close to the beach either ready to head back out, or to head home, if you decide it’s been good enough.

The equivalent of riding out a wave is going to a natural end of a job/position, be it because a project runs out or because you retire or even because your employer goes bankrupt. Riding it out hopefully leaves you with some sense of satisfaction about having done your part, things are in a final state and you can look back and decide whether you switch to a new position, or maybe even retire. But sometimes you leave a wave before it dies out. You could still be riding the wave, but you decide to get off and head back out to catch another wave.

Kicking out is what surfers do when they decide to push the brakes, or take a turn, and get off the wave. There’s various reasons to do this, but the most prevalent one is that they have the idea there are other waves more worthy of their time and energy. In our careers we can do the same thing: we might be going through our jobs and things are moving forward, but at some point we might decide to get off and switch to a position where we hope to get more satisfaction…

So aside from riding out a wave, or kicking out surfers can (and quite often) wipe out. This is what happens when they are forced to quit the wave due to almost always them making a mistake and falling off of their boards. Either by misinterpreting parts of the wave and misjudging whether or not they’ll be able to make it to a next section keep on top of it or by doing some manoeuver that is too difficult or by just the wave closing out, or breaking along itself completely. Either way wiping out is often not fun where in the best case a surfer falls and wastes their wave and in the worst case the wave knocks them off their board and pushes and holds them under water for what always seems (or is) too long.

In jobs you have the same thing… we may paddle and catch a wave that in hindsight was too big. Either we choose a role that was too challenging, or we just didn’t paddle fast enough to catch it properly. Or we may not pay enough attention and fail to notice the section that’s on collapsing on itself, or we mistime a manoeuvre and end up too high or too low to correct and the wave hits us in the face.

Transfer Learning and Milking the Metaphor for all it’s worth

Transfer learning is a concept from machine learning, where you take a model coming from one domain and apply it in another domain. I’m trying to transfer the learnings from surfing to my career. Doing this requires only one thing and that is realizing that your career is a surfing session, man…

This implies that you can wipe out in your career and that’s a scary thought because wiping out sucks. At the same time it can be a comforting thought as soon as you realize that just as you can at any time decide to kick out of a wave to go for a next one, you can always switch jobs. Or just like how after a wipeout you can decide to either head back out to the waves or in to the beach, you can take your burnout as a forced break and check if you want to remain in you current job, or switch to a next one, or stop working altogether. Or just like (in more extreme cases) you can decide that you’re wasting your time on this beach, end the session and head to another beach: you can always re-enroll in school and re-educate yourself.

Looking at myself from this perspective I concluded my last wave was a bit weird. While I did everything right in terms of catching the wave (positioning, power strokes and popping up), I think the wave wasn’t really my type of wave. Maybe a bit too fast, or maybe not providing enough opportunities for fun moves, maybe the COVID crisis made the wave just that bit too fast or steep… But I’m quite sure that there’s waves that are more fit to my style of surfing. At the same time I think I should’ve kicked out earlier and not end up halfway between kicking out and wiping out. I mean, I wasn’t held down by the wave for a long time, and while I’m ready to paddle back out to catch a next wave, it was by no means an elegant exit…

And in the larger scheme of things, the way I surf is similar to the way I navigate my career. I’m always ready to move in a certain direction, without maybe putting enough conscious thought in where that will bring me. In the surf I enthusiastically look where a peak is and hop in in an attempt to get there. It was only my last surf holidays where I started thinking a bit more and from time to time would go out in another direction than where I want to end up, to minimize the hard work. And with wave selection I have the same thing. In surfing, waves come in sets, after a period of no waves, quite often a couple of waves will come one close after the other. One of the basic rules of surfing is to never grab the first wave in a set, because it is never the best wave, but also it allows you to figure out how the other waves are going. In my career I see a similar pattern… My first choice for a program was suboptimal: I started with electrical engineering which by no means was a good fit for me. I can put the work in, though, although again probably I could have spent the energy more effectively: After graduating I spent a lot of energy finding a place to graduate and obtain a PhD. And with regards to being impatient and catching first waves: after graduating I got the opportunity to become an assistant professor that I also did not really question.

There’s a couple of aspects of surfing that play a big role and maybe even can be shoehorned into this metaphor, but at the same time I think maybe it’s more of a follow up thing. Nonetheless, surfing also has a strong social component, as breaks are (almost) always shared by people. Another big component is material, as a surfboard that works great on one wave will not allow you to do anything on another. So there are some parrallels to draw of how sometimes surfers collide or cut each other off and how colleagues might be preventing you from going where you want to go, or parrallels between how certain surfboard work with certain waves, just as certain personalities are made for different jobs. But that’s even more to explain… Nonetheless, looking back at my last wave, I really enjoyed it for a while. The surfers I was surfing with were super social, leaving each other room for positioning, and egging each other on to get the most out of the waves they’re on. But in terms of material I think my surfboard was not the right one. This wave really required me to draw long, straight lines, whereas my surfboard with limited mental resilience really requires some shorter, more twisty/turny waves…

Either way, I’m happy to realize that the wave I was on wasn’t really my type of wave and I had a somewhat sketchy dismount, I’m still looking to head back out and grab a next wave. And it might not the exact same wave, but I’m hoping that it will be not too far from the previous wave while still providing a better ride.

[…] I’m not too embarrassed to admit that I just finished a 16-session therapy with a psychologist, after making the difficult decision to leave academia. For many of us 2020 was a brutal year. I personally was already spread out quite thin before the pandemic and now when COVID forced me to switch my courses from offline to online and back, it resulted in an even higher workload. But parallel to that, the physical distance the lockdown allowed (or forced) me to take provided me with a perspective with a bit of distance. These two factors lead to my decision to leave my position somewhat overworked and with a bit of a depression. […]